Women in the colonial era of Virginia do not garner nearly as much attention as men of the time did. Though the lives of individual women are lesser known than their male counterparts, the roles women filled in the colonial era are well known. There are some women who–through records, writings, and journals—are well enough documented that a pretty accurate portrait can be painted of their lives. Some women of this bygone era even left a lasting enough impression to be viewed as entrepreneurial, ahead of their time, unusually strong (considering how they are generally portrayed), and, in a few cases, are even more commanding than their husbands.

Not many women in the Kennon family stand out as much as their male counterparts. One such woman who does is Elizabeth Worsham Kennon, the wife of Richard Kennon who established the family at Conjurer’s Neck and built Old Brick House. Born in the mid-1600s, Elizabeth Worsham was the daughter of Englishman William Worsham and his wife, Elizabeth Littlebury. Nothing is known about her early life. However, we do know that young women of her time, if they came from a family of some means or were part of a prominent family, would get basic education in reading, writing, and arithmetic. Sometimes, they could also receive education in languages such as French or Latin. Often, ladies learned to play some kind of musical instrument as well. If Elizabeth received this education, it would greatly assist her in the future as a wife and mother, giving her the ability to manage a household and teach her future children. Girls in the colonial period would, at an early age, be taught all that they would need to know on how to become a wife and run a house and plantation.

Sometime between 1675 and 1684, Elizabeth Worsham married Richard Kennon, an up-and-coming merchant who lived at Bermuda Hundred. In 1677, Richard purchased 750 acres of land at Conjurer’s Neck from Christopher Robinson in Henrico County (present day Colonial Heights) and settled there his new family there. Richard and Elizabeth most likely met one another because Elizabeth’s brother, John Worsham, owned land adjacent to Conjurer’s Neck. By 1685, Kennon had likely had their home built at Conjurer’s Neck. The home would become known years later as the Old Brick House, because mariners sailing on the Appomattox River listed the house on their navigational charts as “The Brick House”. At this time, Henrico County represented the limits of colonization, so land to the west was considered the frontier of the colony.

As the lady of the house, Elizabeth would have been responsible for the daily operations and happenings in the home. Since it is documented that the Kennon family owned slaves, Elizabeth would have been responsible for the organizing and tasking of the domestic enslaved people. Sometimes, women would take part in assisting in jobs and tasks involved in the home. Colonial women would brew beer, help in preparing meals (especially if it were a big meal if there was an event or gathering at her home), sewing, tending to gardens, and tending to the sick on her home plantation. Despite all the things women in colonial days were responsible for, if she were a well-off woman—as Elizabeth most assuredly was—she would still be expected to maintain the appearance of a life of leisure.

Education of the children would also fall to Elizabeth. In colonial days, women gave their children their early education in reading, writing, arithmetic, and religious teaching. Daughters would also be taught early skills that they would need when they would marry and have a home to run. More formal education would come at the hands of tutors if a family could afford to hire one, or they could be sent to a neighboring plantation that had a tutor on site to receive more formal education.

Being adherents of the Anglican Church of England, the Kennon family attended worship services across the Appomattox River at Bristol Parish, established in 1643 and served the counties of Charles City, Henrico, Prince George, and Dinwiddie. Two of Richard and Elizabeth’s sons, William and Richard, served as vestrymen of Bristol Parish.

Richard Kennon died in 1696. He was likely in his forties or early fifties when he died; life expectancy was not very high in colonial times. At his death, he owned thousands of acres of land, including an 8,000 acre grant he obtained on April 1, 1690 for having furnished passage to ninety indentured servants and seventy enslaved individuals (under the headright system in colonial Virginia, a person received 50 acres of land for every individual, indentured servant or enslaved person, brought to the colony). In colonial Virginia, according to Edmund Morgan, “a single woman might own property, contract debts, sue and be sued in court, and run her own business, but a married woman, so far as the law was concerned, existed only in her husband. If he died before she did, she was entitled to a life interest in a third of his property.” Often a widow would remain on the main plantation the family lived on, which would eventually go to the eldest son. In this case, Elizabeth deeded Conjurer’s Neck to her eldest son, William, on March 1, 1710. On April 24, 1703, Elizabeth and several other men were granted 4,000 acres of land in Henrico County for having furnished passage of eighty persons. Some of this land was on Winterpock Creek, which will play a role in a deed Elizabeth made to her son, Richard, in 1719.

As previously mentioned, a single women could own businesses. Elizabeth was one of the few women to show her industrious nature. Despite the early loss of her husband, she continued to manage the family’s lands, indentured servants and enslaved people, probably with the help of some of her children, other relations and friends. Having been witness to her deceased husband’s business acumen, Elizabeth likely learned much from him and learned what it took to be entrepreneurial. At some point, she began to operate a ferry a few miles upriver from Conjurer’s Neck, near Point of Rocks, on the Appomattox River. This ferry served to transport people across the Appomattox River to destinations in all directions, as well as parishioners who attended church services at Bristol Parish. For the operation of said ferry, she was paid by Bristol Parish. The record keeping for Bristol Parish meetings begins in 1720. At this point, Elizabeth had already been operating the ferry; for how many years prior to 1720 is not known. The 1720 entry in the Bristol Parish Register lists the following:

Bristoll P’ish—ss: At A Vestry Held At the Chappell Xbr 17th—1720…

…It is ordered that the ferry be continued to Mrs. Eliz. Kennon the next ensuing years as formerly…

…To Mrs. Eliz. Kennon for keeping the ferry…2,500 [lbs. of tobacco] 200 [casks to pack the tobacco in]

All of the following entries for what Elizabeth was paid in tobacco read much like the above listing in the Bristol Parish Register. She operated the ferry until 1735 for the parish. After 1735, Elizabeth no longer received compensation for the operation of the ferry. In 1736, according to records in the register, construction began on a new chapel and beginning in 1738, the parish minister, George Robertson began getting compensated for ferriage. From 1720 until 1735, Elizabeth was paid a total of 61,200 pounds of tobacco for her management of her ferry by Bristol Parish. Her son, William, one of the parish vestrymen, in the same time period was paid 100,866 pounds of tobacco for his involvement and efforts in the parish. As one can see, the Kennon family benefited greatly from their involvement in Bristol Parish. In colonial Virginia, there was no currency. Tobacco served as the currency of the colony and was sent to England. In return for that tobacco, merchants would give credit to colonists so that they could purchase the commodities they needed and the luxury items they wanted.

In a 1719 deed of gift, Elizabeth grants to her son, Richard and his wife to be, Agnes Bolling, 444 acres of land at “Wintepock”, part of the grant above mentioned that Elizabeth had received in 1703. In this deed of gift, she also gave the couple 107 acres of land at the ferry; Elizabeth would continue to operate and run the ferry as evidenced by the records of the Bristol Parish vestry. Another gift Elizabeth gave Richard and Agnes were, “Seven negroes Viz. Sam, Tony Moll Amy Frank Jenny Tom boy To have and to hold.” It was a common practice in colonial Virginia to be gifted enslaved people and/or land as wedding gifts.

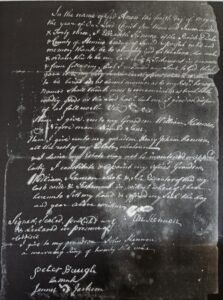

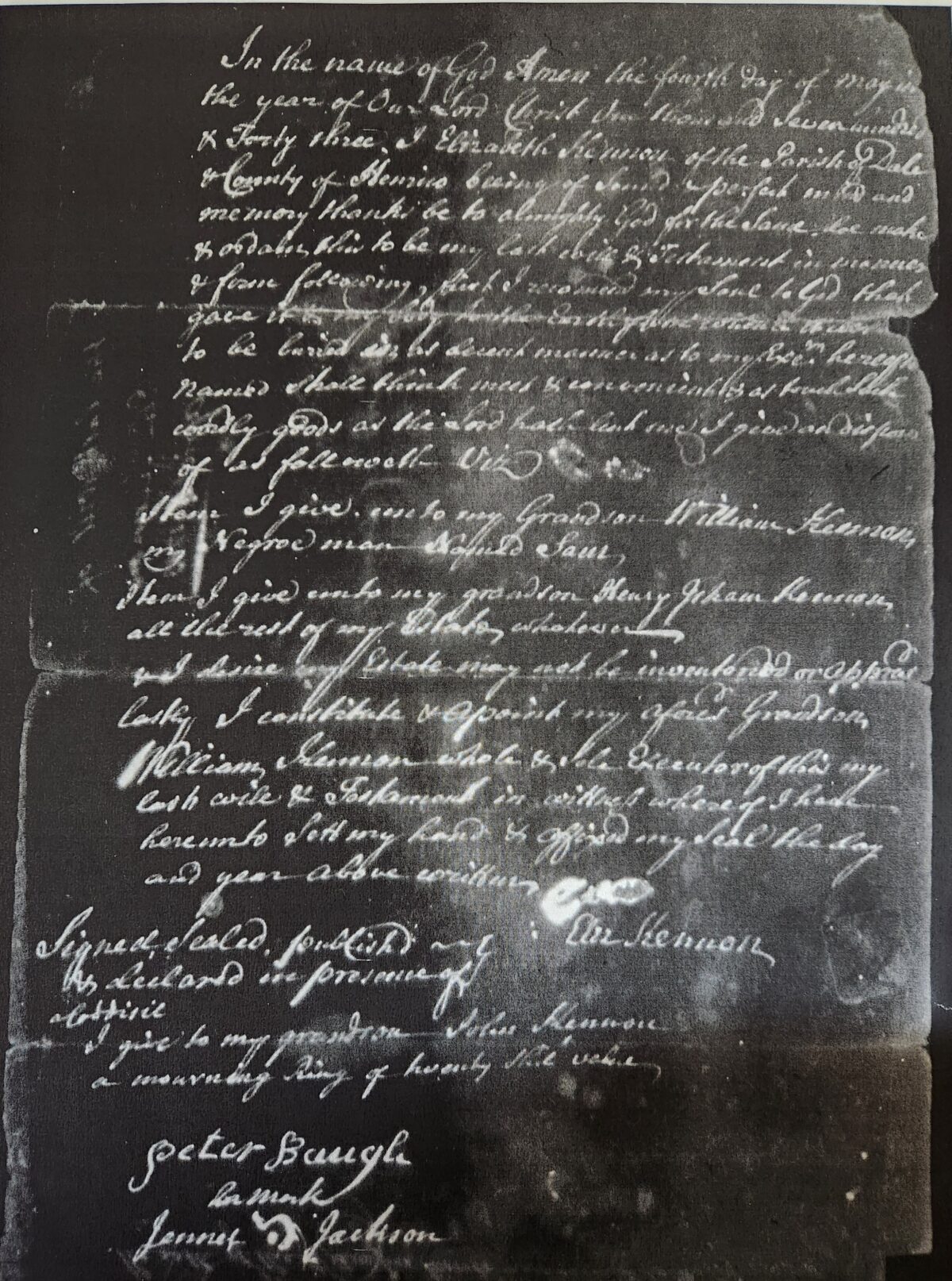

Elizabeth, born in the mid-1600s, wrote her will May 4, 1743 and died shortly thereafter. This would have put her at around at least eighty years of age, well beyond the life expectancy for the time period, not to mention she outlived her husband by an amazing 47 years!!! She must have had a strong will, body, and constitution. The will she makes is pretty simple in its verbiage and few bequests are made. Below is a transcription of Elizabeth’s will:

In the name of God Amen the fourth day of May in the year of Our Lord Christ One Thousand Seven hundred & Forty three I Elizabeth Kennon of the Parish of Dale & County of Henrico being of Sound perfect mind and memory thanks be to almighty God for the Same doe make & ordain this to be my last will & testament in manner & form following, First I recommend my Soul to God that gave it & my body to the Earth _____________ to be buried in a decent manner as to my Exe hereafter named shall think most & convenient as such _____ worldly goods as the Lord hath _____ me I give and dispose of as followeth Viz

Item I give unto my Grandson William Kennon my Negroe man Named Saul.

Item I give unto my grandson Henry Isham Kennon all the rest of my Estate whatever & I desire my Estate may not be inventoried or Appraid

Lastly I constitute & apoint my aforesd Grandson William Kennon whole & Sole Executor of this my last will & Testament in witness where of I have hereunto Sett my hand & affixed my Seal the day and year above written.

Eliz Kennon

Signed, Sealed, publishd

& _____ in presence of

Coddicil

I give to my grandson John Kennon

a mourning Ring of _____ Shil value

Peter Baugh

his mark

James Jackson

As was common in wills of the time period, Elizabeth gave one of her enslaved people, a “man Named Saul,” to her grandson, William. She gave the remainder of her estate (if you will remember previously mentioned that typically widows retained a one-third interest in their deceased husband’s estate) to her grandson, Henry Isham Kennon. It is unknown what happened to Henry’s portion of the estate, as he himself died unmarried in 1747. Do you notice anything missing? She did not make any bequests to her children. Why is that? Likely because her children were more than well provided for at the death of their father. Another thing that is interesting of note in this will, the codicil at the end in which Elizabeth bequests a mourning ring to her grandson, John. This mourning ring is likely a ring she purchased or was given at the death of her husband Richard. The last thing of interest in her will is that she wished for her estate to not be inventoried or appraised. In the many last wills and testaments that I have read and transcribed over the years, this is the first time that I have encountered this. Why would she not want it inventoried or appraised? Did she have a lot to her estate that she did not want her children to get? Did she have something to hide? We will likely never know the answer to these questions since we do not know what her estate included.

Thus ended the life of a woman who has left many thousands of descendants today. She lived a long, well lived life, well beyond the length of nearly all those of her time. In a time when most women did not have opportunities as business owners, she went on to become one of the few who had the opportunity and successfully ran with that opportunity, operating her ferry for at least fifteen years. One could say she was a woman ahead of her time.

References

Chamberlayne, Churchill Gibson. The Vestry Book and Register of Bristol Parish, Virginia, 1720-1789. Richmond, VA: Churchill Gibson Chamberlayne, 1898.

Kennon, Elizabeth, Virginia. Colonial Land Office., and Library of Virginia. Archives. Land Grant 24 April 1703. N.p., 1703.

Kennon, Elizabeth. “Tom, etc.: Deed, 1759 (1108028_0018_0003). Virginia Untold: The African American Narrative Digital Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va.”

Henrico County (Va.) Deeds, 1650-1931 (bulk 1813-1931), 1719.

Kennon, Elizabeth. “Henrico County Miscellaneous Court Records, Vol. 4, 1738-1746”, reel 2, page 1225, 1743.

Morgan, Edmund S. Virginians at Home: Family Life in the Eighteenth Century. Williasmsburg, VA: The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1952.

Sorley, Merrow Egerton. Lewis of Warner Hall: The History of a Family. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co. Inc., 1991.

4 replies on “Elizabeth Worsham Kennon: Independent Woman”

Enjoyed this article! Great job.

Glad you enjoyed it Cecelia (mom)!!!

Enjoyed reading this.

Glad you enjoyed it, Augusta!!!