Richard Kennon and his role in the peculiar institution

The institution of slavery has been a part of Old Brick House going back at least to when the Kennons first settled Conjurer’s Neck. Though his early origins are sketchy, Richard Kennon was in Virginia by 1670. He initially obtained land at Bermuda Hundred and near Rochdale. Kennon had a warehouse at Bermuda where he was engaged as a successful merchant. On October 19, 1677, Richard Kennon purchased Conjurer’s Neck from Christopher Robinson. As well as being a merchant, he was also an agent and attorney for William Paggen and Company, a London merchant heavily engaged in trade with Virginia.

What kind of trade was Paggen engaged in? Tobacco, slaves, rum, sugar, and any other wares he had in his London warehouse. Kennon and a Quaker by the name of John Pleasants both served as agents for Paggen and Company, their role being receivers and sellers of the slaves that Paggen and Company sent to the colony. In a letter dated June 21, 1684 by William Byrd, he writes “Mr. Paggin sent about a fortnight since into these parts, 34 negroes with a considerable quantity of dry goods and seven or eight tons of rum and sugar, which I fear will bring our people much into debt and occasion them to be careless with the tobacco they make.” Kennon and Pleasants made a petition to be exempt from paying taxes on these slaves sent to Virginia. As regards their petition, they were awarded the following from the Henrico County Court:

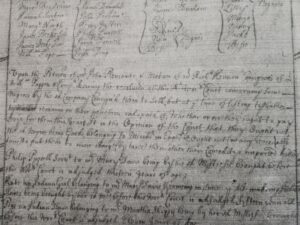

…desiring the resolution of this Right Worshipful Court concerning some Negroes of the said Company consigned them to sell, but at ye time of listing tithables, remaining in their possession undisposed of: It is the opinion of the Court that the said Kennon and Pleasants ought not to pay levy for them this year, because the said Negroes being goods belonging to merchants in England, ought not in any reasonable time to put them to more charge by taxes than other of their commoditites imported hither.

As agents for Paggen and Company, these thirty-four slaves were delivered to Kennon and Pleasants in Virginia to be sold by them. What happened to these slaves is unknown. They were likely sold by Kennon and Pleasants, some of them may even have been purchased by these two men.

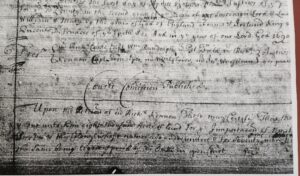

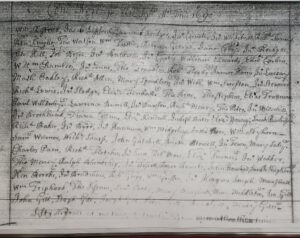

On April 1, 1690, Kennon received a land grant of 8,000 acres for having transported ninety white people and as the land grant states “fifty Negroes at one time & twenty Negroes more at another time.” The grant actually lists all of the indentured servants by name, but not those to be sold as slaves. Under the headright system, for every person brought to the colony of Virginia, whether enslaved or indentured, the person furnishing passage of said persons was to receive fifty acres of land per person (the headright system would be abolished in 1779, during the Revolutionary War). This is one of the ways Richard Kennon was able to amass large amounts of land. Aside from bringing in and selling large numbers of slaves, Kennon also brought in a large number of indentured servants as well.

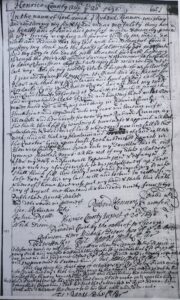

A common occurrence in the era that slavery occurred was for owners to give slaves and land as marriage gifts and when a slave owner made their wills, it was very common for them to devise slaves to their heirs as they would land and livestock. When Richard Kennon made his will on August 6, 1694, he gave “unto my Daughter Judith one younge feemale Negro.” Notice how Richard does not mention the slave by name. It was common that slave owners would not mention a slave by name as it gives them an identity. One of the ways slave owners asserted their dominance over their bondpeople was to take away their identity, any way for them to be an individual, a person. For more information on the will of Richard Kennon, see the following link: The Will of Richard Kennon of Conjurer’s Neck | Todd’s Archives.

References

Bruce, Philip Alexander. Economic History of Virginia in the Seventeenth Century. New York, NY: MacMillan and Co., 1896.

Hardin, William Fernandez. “Litigating the Lash: Quaker Emancipator Robert Pleasants, The Law of Slavery, and the Meaning of Manumission in Revolutionary and Early National Virginia.” PhD dissertation, Vanderbilt University, 2013.

Henrico County Court. “Henrico Co. Order Book (& Wills), 1678-1693.” Reel 53, page 163, 1684.

Henrico County Court. “Henrico Co. Order Book (& Wills), 1678-1693.” Reel 53, pages 326-327, 1690.

Morgan, Edmund S. Virginians at Home: Family Life in the Eighteenth Century. Williamsburg, VA: The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1952.

No author. Slave Trading to Virginia. America In Class, National Humanities Center, https://americainclass.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/REV-Slave-Trading-to-VA.pdf.